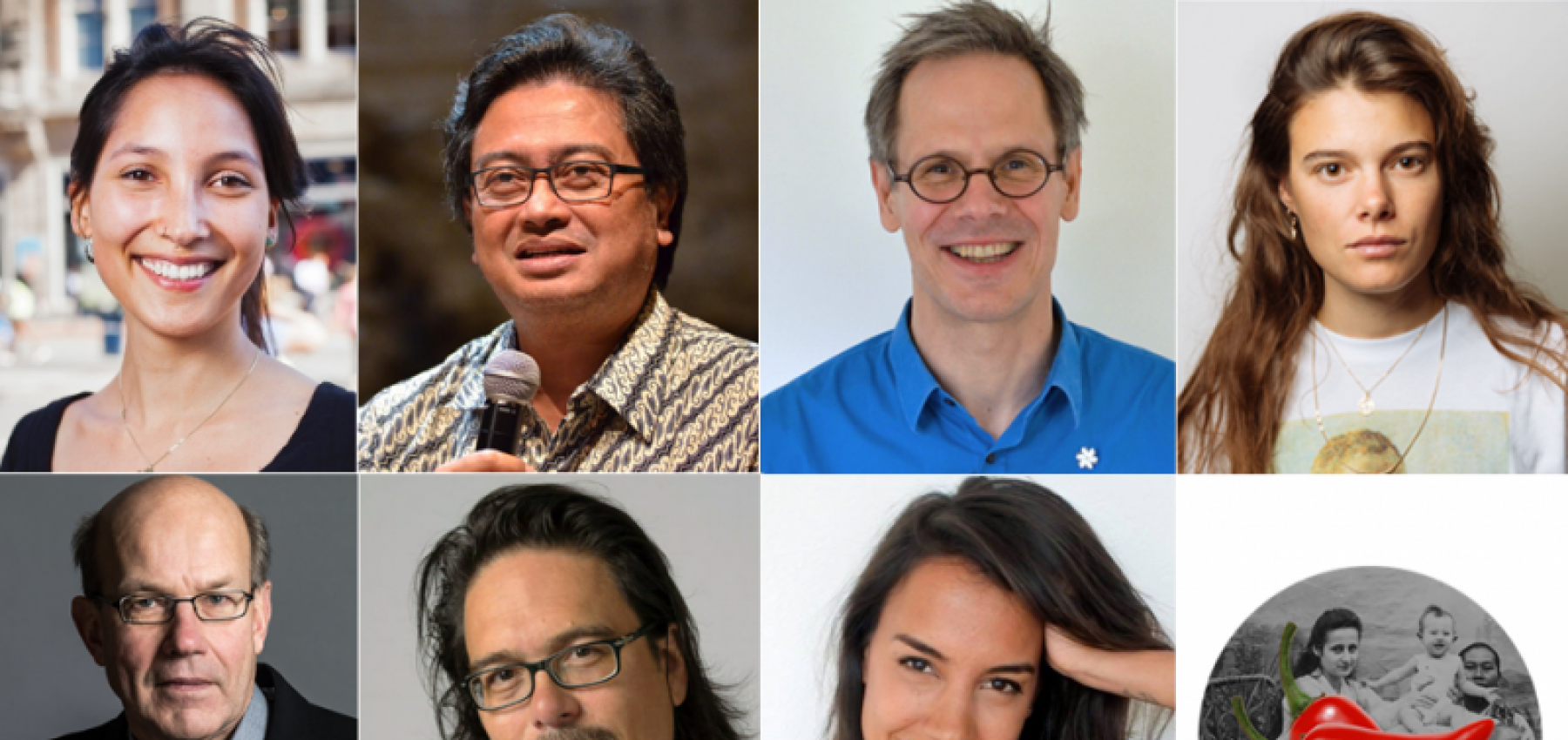

On Sunday, 25 November, the Indisch Herinneringscentrum held a meeting entitled ‘Indië Tabee?’ This gathering concluded the Gepeperd Verleden series of meetings looking at what a shared colonial heritage means from various perspectives. Researcher Remco Raben, who is involved with the Political Administrative Context project, and Stephanie Welvaart from Witnesses & Contemporaries took part in the meeting.

Our own past first

The discussions about the colonial past continue unabated. While criticism of colonialism is nothing new, it would appear that accusations regarding the fundamental inequality, violence and racism of colonial rule are only on the increase. Whether ‘the Netherlands’ has actually dissociated itself from its colonial views of the world is also a question that is being asked more frequently. Today, there are still many people living in the Netherlands who actually experienced the colonial era. This begs the question of how their personal memories relate to the shifts in understanding and to the debates about the colonial past. Can happy memories of an Indonesian childhood go hand in hand with criticism of colonialism? This issue was the focus of the fifth and final debate in a series entitled ‘Gepeperd Verleden’ (A Peppered Past) held over the past year and organized by the Indisch Herinneringscentrum.

Personal memories are not held in isolation. They are in all kinds of ways intertwined or become entangled with other forms of historical consciousness, such as historiography and moral judgements made on colonialism. These three levels are mixed up with each other, leading to friction, a lot of confusion and debate.

This final edition of the Gepeperd Verleden series made this apparent, too. Guesting at the event was writer Kester Freriks, who in his recent pamphlet Tempo Doeloe, een omhelzing had argued for a ‘justification’ of the colonial past. After all, countless people cherish fond memories of their childhood years in the Dutch East Indies. While Freriks recognizes that there were also darker sides to the colonial past, he experiences the growing anticolonial criticism as being one-sided. Ultimately, he reasons, colonialism was not always quite as bad as is often claimed.

This argument is problematic, as it confuses personal memories with claims about the nature of the colonial regime. During the discussions, it became clear that in order to disentangle oneself, a clearer distinction needs to be made between the various levels of meaning given to the colonial past. This means also being able to confront your own memories with the stories of others, with more general histories, and with the shifts of morality through time. The fact is that fond memories of a colonial childhood, however indisputable they may be, are linked to the position that that person held within colonial society.

Memories, histories and morals grate against each other. And particularly at those points in stories where there is tension, where things become uncomfortable, there is a wealth of information to be found. As such, recollections of Tempo Doeloe, as they live on in the Netherlands, can form the starting point for further research. This is because these particular stories make clear how the colonial system worked and how it continues to affect memories. How do people look back on the colonial era? What do people talk about, and what do they not mention? Who plays the leading role in such memories, and who is assigned a supporting part?

One’s own perspective naturally predominates all memories. But a typically colonial characteristic is not questioning or only barely questioning one’s own privileges and the inequalities in society, which, after all, greatly determined or had a considerable influence on personal experiences and memories. It is therefore essential to ensure that space is accorded to the various different perspectives and that these all stand side by side. In order to arrive at a balanced history, stories are needed that challenge the dominant Dutch narrative and show us our blind spots.

However, the idea that all personal stories taken together form history is far too simplistic. A history can never do justice to all individual experiences. We must also be aware of the fact that choices always need to be made, which means that some stories do get heard or told, while others do not. Certain personal and collective stories are more dominant in the public representation of the colonial past, and some perspectives have a stronger presence than others. As the Indonesian writer and journalist Joss Wibisono remarked during the discussion at the Gepeperd Verleden event, Indonesians are almost always extras in the Dutch stories told about the colonial era.

Those gathering and telling stories bear a great responsibility to do justice to the complexity of colonial recollection, and to allocate a place not only to the personal experiences of Dutch nationals but also to those of people from a variety of backgrounds, such as Indonesians, Indo-Europeans, Chinese nationals and others. Personal stories can then serve to correct and highlight, and form a means of escaping ideas about the past that are often so schematic and dominant.